Comparing HSAs, FSAs, and LSAs #

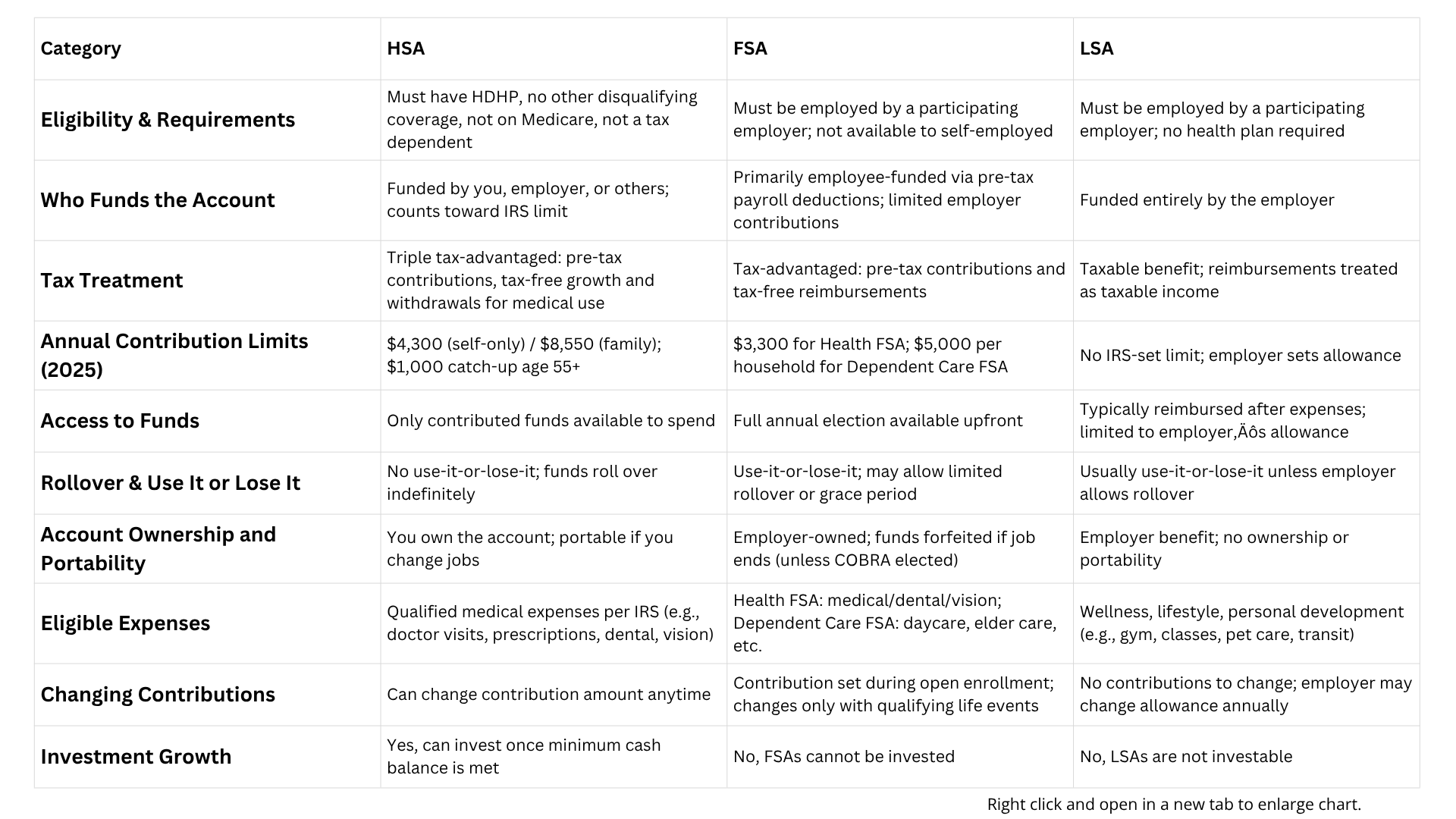

HSAs, FSAs, and LSAs each have distinct features. The infographic below highlights key differences between HSAs and FSAs (the two tax-advantaged health accounts). Notice differences in eligibility, ownership, contribution limits, and rollover rules. LSAs, which are not tax-advantaged medical accounts, differ even further – for instance, only employers fund them and they cover non-medical expenses. We’ll outline LSA differences in the text that follows.

Key differences between an HSA and an FSA (LSAs differ further as described below).

Below is a side-by-side comparison of major factors for HSAs vs FSAs vs LSAs:

Eligibility & Requirements

HSA: Must be enrolled in a qualified high-deductible health plan (HDHP). Cannot have other disqualifying coverage (including a general-purpose FSA), and cannot be on Medicare or claimed as a tax dependent.

FSA: Must be an employee of an employer that offers an FSA. Available to most benefits-eligible employees; self-employed not eligible. No specific insurance plan enrollment required for Health FSA (though having any health plan helps ensure you have expenses to use it on!).

LSA: Must be an employee of an employer that offers an LSA program. No health plan or insurance requirements. The employer sets any additional eligibility rules (for example, might need to be full-time or have passed a probation period, depending on the plan).

Who Funds the Account

HSA: Funded by you, your employer, or anyone on your behalf. Contributions can come from payroll deductions, lump sum deposits, or employer contributions like seed money or wellness incentives, all counting toward your annual limit.

FSA: Funded by you (the employee) via pre-tax payroll deductions. Employers may contribute in some cases, but it’s primarily employee-funded. Each spouse can have their own FSA through their jobs, but funds are not shared between spouses.

LSA: Funded entirely by the employer. Employees do not contribute. The employer allocates a certain dollar amount for each employee’s use.

Tax Treatment

HSA: Triple tax-advantaged: contributions are pre-tax (or tax-deductible), growth is tax-free, and withdrawals are tax-free when used for qualified medical expenses. (Withdrawals for non-qualified expenses are taxed + 20% penalty if under age 65.)

FSA: Tax-advantaged: contributions are pre-tax (exempt from income and payroll taxes), and reimbursements for eligible expenses are tax-free. There’s no investment component, just tax-free in and out for spending within the year.

LSA: Taxable benefit: reimbursements are generally treated as taxable income to the employee (since they don’t meet IRS tax-free benefit criteria). The employer’s contributions are made post-tax. Essentially, LSA funds are like a bonus earmarked for wellness (the company may gross-up or just add it to your W-2). One exception: if an LSA includes something like educational assistance or certain transit subsidies, those specific pieces might fall under existing tax-free limits, but most LSA items are taxable.

Annual Contribution Limits (2025)

HSA: Yes – limited by IRS. For 2025, up to $4,300 if you have self-only HDHP coverage, or $8,550 if you have family HDHP coverage. People age 55+ can put in an extra $1,000 (“catch-up” contribution). These limits usually adjust annually.

FSA: Yes – limited by IRS. For a Health Care FSA, the 2025 cap is $3,300 per employee (regardless of single or family status). Dependent Care FSA is capped at $5,000 per household (unchanged, set by law). Employers can choose lower caps for their plan, but not higher. You elect an amount up to the limit each year.

LSA: No federally set limit. The employer decides how much to offer. It could be $200, $1,000, or more – it’s up to the company’s budget and objectives. There’s no tax law imposing a maximum (since any amount is taxable to you anyway).

Access to Funds

HSA: Only the money that has actually been contributed is available to spend. Your HSA balance grows as you and/or your employer deposit funds (much like a bank account). You can only use what’s in the account at that moment – no borrowing ahead from future contributions.

FSA: Full annual election is available upfront (for Health FSAs). If you elected $3,000 for the year, that full amount is accessible for claims on day one of the plan year, even though you haven’t contributed it all yet. (Dependent Care FSAs work on a pay-as-you-go basis; you can only get reimbursed up to what has been deducted so far.)

LSA: Typically, employees get reimbursed after spending their own money on eligible items. Some employers might fund an LSA account or card that can be drawn down, but commonly you submit receipts and the company pays you back up to your allowance. You can only get reimbursed up to the set allowance (e.g., if the LSA yearly cap is $500, that’s all you can use, and you can’t get more even if you have more eligible expenses).

Rollover & “Use It or Lose It”

HSA: No use-it-or-lose-it – all funds roll over year to year indefinitely. There is no expiration on HSA money; unspent funds simply remain in your account for future healthcare needs. This allows balances to grow over time.

FSA: Use-it-or-lose-it applies. Generally, you forfeit any unspent money at the end of the plan year. However, your employer’s plan may offer either a short grace period or a carryover of a limited amount (e.g. $660 can carry from 2024 to 2025). Any excess beyond the allowed carryover is lost. It’s important to plan FSA contributions carefully to avoid forfeiture.

LSA: Usually use-it-or-lose-it for each plan year as well. Unused LSA allocations typically don’t carry over unless your employer explicitly allows some rollover. If you don’t use the available funds by year-end, the opportunity is gone (and the employer keeps the unspent money). LSAs are meant to encourage use of the benefits annually.

Account Ownership and Portability

HSA: You own the HSA. It’s a personal bank account in your name. If you change jobs or retire, the HSA stays with you (you might lose the ability to contribute new funds if you’re no longer HSA-eligible, but the existing money remains yours). You can spend it down over your lifetime on eligible expenses.

FSA: Employer-owned arrangement. The FSA is tied to your employer. If you leave the company, any unused FSA funds are forfeited to the employer (unless you elect costly COBRA continuation for a health FSA). FSAs do not move with you between jobs. Each new employer, if they offer an FSA, means starting a new account/fresh election.

LSA: Employer-provided benefit, not a personal account. If you leave the job or the program ends, you can no longer use any remaining LSA funds. There’s nothing for you to “take with you,” since reimbursements were essentially company funds. It’s tied entirely to your employment.

Eligible Expenses (What You Can Use It For)

HSA: Qualified medical expenses as defined by the IRS (the same types of expenses you could deduct on taxes or use an FSA for). This includes most out-of-pocket medical, dental, and vision care costs for you and your family. Common examples: doctor’s visits, lab tests, hospital bills, surgery, prescription drugs, insulin, over-the-counter medications and first aid supplies, therapy, dental treatments, eyeglasses, contact lenses, etc. HSAs are for health expenses only – you cannot use them for general wellness or non-medical costs.

FSA: Qualified health expenses (for Health FSA) – very similar list to HSA above, covering medical/dental/vision for you and dependents and/or Dependent care expenses (if you have a Dependent Care FSA) – which include daycare, babysitters, day camps, elder care facilities, etc., for a child under 13 or a disabled dependent so that you can work. Each FSA type’s funds can only be used for that respective category. Also, FSAs cannot be used to pay insurance premiums or cosmetic procedures, and any expense must be within the current plan year.

LSA: Wellness, lifestyle, and other personal development expenses as defined by your employer. Non-medical by nature. Typical categories include fitness (gym memberships, workout classes, equipment), wellness (nutrition programs, weight loss programs, mental health apps, massages), personal growth (educational courses, hobby classes), family and life (child or elder care support, pet care, travel or commuting costs, entertainment events). LSAs intentionally cover things that HSAs/FSAs do not, providing a broader definition of well-being. They generally cannot be used for expenses that health FSAs or insurance would cover (and if an expense is health-related, you’d usually use HSA/FSA for the tax break first).

Changing Contributions

HSA: You can change your contribution amount at any time during the year (increase, decrease, stop, restart), as long as you don’t exceed the annual max. This offers flexibility if your financial situation or needs change.

FSA: You choose your annual contribution during open enrollment, and that election is locked in for the year. You generally cannot change it mid-year unless you have a qualifying life event (such as marriage, divorce, birth of a child, etc.) that allows an adjustment. This is why planning is important; you have to estimate your yearly expenses in advance.

LSA: There’s no contribution from your side, so nothing for you to change. The employer might adjust the allowance year to year, but as an employee you just use whatever amount is offered.

Investment Growth

HSA: Yes, many HSAs allow you to invest funds in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc., once you have a minimum balance (often around $1,000 or $2,000) in cash. Invested funds can grow and earn interest or gains tax-free, providing potentially significant long-term growth. An HSA can effectively become a supplemental retirement healthcare account thanks to this investment feature.

FSA: No, FSAs do not have an investment option. They are a simple spend-and-reimburse account, and the money does not earn interest. Since funds are short-term and forfeitable, there’s no opportunity or mechanism to invest FSA dollars.

LSA: No, there’s no investment component. The funds are not really “yours” to invest; they are just a reimbursement pool for expenses. Typically, you aren’t given the LSA money upfront to invest – you only receive it when you file a claim for reimbursement.

In summary, HSAs and FSAs share the goal of using pre-tax money for expenses but differ in ownership, flexibility, and longevity of funds. LSAs are a different animal altogether: a taxable employer perk for lifestyle benefits. HSAs are best viewed as a long-term personal health savings/investment account, FSAs as a year-to-year budgeting tool for predictable expenses, and LSAs as a wellness benefit to utilize for your personal improvement.