Overview #

Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), Dependent Care Flexible Spending Account (Dependent Care FSA or DCFSA), and Lifestyle Spending Accounts (LSAs) are four types of Tax-Advantaged and Employer-Sponsored Spending Accounts that can help you save money or get reimbursed for certain health and wellness related expenses.

Each account type has different rules, tax advantages, and eligible uses. In this guide, we’ll guide you through what HSAs, FSAs, DCFSA, and LSAs are, how can use them, how they work, and how they compare. We’ll also provide tips for maximizing your potential usage of each, and guidance on choosing the right account type for your situation.

What is a Health Savings Account (HSA)? #

A Health Savings Account (HSA) is a special savings account you can use for health care expenses.

It offers triple tax advantages: contributions are made pre-tax (or tax-deductible), the money in the account grows tax-free, and withdrawals are tax-free when used for qualified medical costs. Think of an HSA like a 401(k) for healthcare – it helps you save for medical expenses now and in the future.

HSAs are paired with High Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs), which have higher deductibles but often lower monthly premiums. Because HSAs rollover, HDHPs often have lower monthly premiums compared to traditional health plans, and contributions, earnings, and withdrawals to an HSA are tax-free, HSAs are a powerful way to save for future healthcare expenses.

Eligibility #

To contribute to an HSA, you must be enrolled in a High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

This is an insurance plan with a higher deductible than standard plans. You generally cannot have other comprehensive health coverage (like a standard health plan or general-purpose Flexible Savings Account (FSA) alongside an HSA. You also cannot be enrolled in Medicare, or be claimed as a dependent on someone else’s tax return. If you meet these criteria, you’re eligible for an HSA.

How It Works #

An HSA is owned by you, the account holder – not by your employer.

You (and your employer or anyone else) can contribute money up to an annual limit set by the IRS.

In 2025 the HSA contribution limit is $4,300 for self-coverage, $8,550 for a family, with an additional $1,000 catch-up allowed if you’re 55 or older.

These limits typically increase a bit each year, adjusting for inflation. You can change your contribution amount at any time during the year. For instance, you can make adjustments to your payroll deductions, giving you flexibility to save more or less as needed.

Using HSA Funds #

Money in an HSA can be used to pay for a wide range of qualified medical expenses for you, your spouse, and dependents. Qualified expenses include things like doctor visits, hospital bills, certain wellness services, prescription drugs, dental and vision care, and many over-the-counter items.

HSA funds generally cannot be used to pay insurance premiums, except in special cases such as COBRA coverage or certain Medicare premiums.

Typically, you’re provided a debit card or online bill-pay from your HSA bank to pay providers directly, or you can pay out of pocket and then reimburse yourself from the HSA.

There’s no deadline for reimbursements – you could save your receipts and withdraw HSA funds years later for those expenses, if you choose, allowing the balance to grow in the meantime, which is an advantage of this type of account.

Tax Benefits #

Contributions to an HSA are pre-tax

This means the contribution are taken from your gross income, reducing your taxable income (i.e. you don’t pay federal income tax, Social Security, or Medicare taxes on HSA payroll contributions).

Any interest or investment earnings in the HSA are also tax-free.

Withdrawals are tax-free as long as they are used for qualified medical expenses. This triple tax advantage is unique to HSAs.

If you withdraw HSA money for non-medical purposes, you’d owe income tax and a 20% penalty (if under age 65).

After age 65, non-medical withdrawals are taxed as income but not penalized – essentially the HSA can act like a traditional retirement account if needed.

Rollover and Portability #

Unused HSA funds roll over automatically each year

There is no “use-it-or-lose-it” rule. Your HSA balance stays with you indefinitely until you spend it. You own the HSA, so if you change jobs or health plans, the money is still yours to use for future medical expenses. This makes HSAs a powerful long-term savings tool for healthcare costs, including in retirement.

Investing HSA Funds #

Many HSA providers allow you to invest your HSA money in mutual funds or other investments once your balance exceeds a certain threshold. This means your HSA can grow over time, similar to a 401(k). Any investment gains are tax-free, as long as they stay in the account. Investing your HSA can be a great savings strategy if you don’t need to spend all the funds immediately on medical bills.

Summary #

An HSA is a personal, tax-advantaged savings account for health expenses.

It requires a high-deductible health plan, but in return it offers significant tax savings and the ability to build a nest egg for future healthcare needs.

HSAs are best for those who want to save on taxes and possibly invest money for medical costs down the road, and who are comfortable with the out-of-pocket risks of a high-deductible insurance plan.

What is a Flexible Spending Account (FSA)? #

A Flexible Spending Account (FSA) is an employer-sponsored account that lets you set aside pre-tax money from your paycheck to use on eligible expenses.

The two most common types are Health Care FSAs (for medical-related expenses) and Dependent Care FSAs (for childcare or dependent adult care expenses). FSAs are sometimes called “flexible spending arrangements.” They can save you money on taxes by using pre-tax dollars for costs you would have paid anyway with after-tax money.

Eligibility #

FSAs are available only if offered by your employer as part of your benefits; self-employed individuals generally cannot have an FSA.

You don’t need to be enrolled in a specific health insurance plan to have a general Health Care FSA – any benefits-eligible employee whose company offers an FSA can participate. (However, note that if you are enrolled in an HSA, you typically cannot enroll in a full Health Care FSA at the same time, because IRS rules prevent dual use. You might be offered a limited-purpose FSA in that case, which we’ll touch on later.) Dependent Care FSAs are also employer-dependent and subject to IRS rules.

How It Works #

An FSA is funded by setting aside a portion of your paycheck before taxes are taken out.

You decide during your open enrollment period how much to contribute for the year (up to the IRS limit). That annual election is then deducted in equal installments from your pay throughout the year.

The key benefit is FSA dollars are never taxed

This gives you an immediate discount on your expenses equal to your tax rate. Depending on your employer’s plan, they may also contribute to your FSA (though this is less common, or might be a modest amount).

Notably, for a Health Care FSA, the full year’s elected amount is available to you from day one of the plan year – even though you haven’t paid in all that money yet.

For example, if you elect $1,200 for the year, you can use the entire $1,200 for an eligible expense in January, and then you “pay it back” via paycheck deductions over the rest of the year. (Dependent Care FSAs work differently: funds are only available as they are contributed each pay period.)

Using FSA Funds #

Health Care FSA funds can be used for qualified medical expenses very similar to HSA-eligible expenses: doctor copays, health insurance deductibles, prescriptions, dental care, vision care (glasses, contacts), medical supplies, wellness services and products, many over-the-counter medicines, menstrual products, and more.

Essentially, any health expenses that would qualify as deductible medical expenses under IRS rules (IRC Section 213(d)) are FSA-eligible, with the exception of insurance premiums. You can use your FSA to pay for your own expenses, or those of your spouse or dependents. Typically, FSAs offer a debit card for convenience, or you can submit receipts for reimbursement through your FSA administrator. You must keep receipts/documentation as proof that purchases were eligible, in case the administrator or IRS needs to verify them.

Tax Benefits #

With an FSA, contributions are pre-tax

This means you do not pay federal income or payroll taxes on the money you put in. This saves you roughly 20% to 40% on each dollar (depending on your tax bracket) compared to paying out-of-pocket with after-tax money.

Withdrawals are tax-free as well, as long as they are for eligible expenses. In other words, an FSA effectively gives you a discount on medical or dependent care costs equal to the taxes you would have paid on that income. Example: if you put $2,000 into a health FSA and you’re in a 22% federal tax bracket, you save about $440 in taxes that year.

Contribution Limits #

The IRS sets a limit on how much you can contribute to an FSA each year (adjusted annually for inflation). For a Health Care FSA, the limit for 2025 is $3,300 per employee (up from $3,050 in 2024).

If you’re married and both spouses have separate FSA plans at work, each can contribute up to the max (so a couple could set aside up to $6,600 total if both employers offer FSAs).

Dependent Care FSA contributions are capped by law at $5,000 per household per year (or $2,500 if married filing taxes separately). Important: These limits apply to contributions; they don’t limit how much your employer can reimburse you if you have valid claims (the reimbursement is naturally limited by what you contributed and any employer seed money).

“Use-It-or-Lose-It” and Rollover Rules #

One of the biggest differences between FSAs and HSAs is that FSAs are generally subject to a “use it or lose it” rule.

Funds in an FSA typically must be used within the plan year, or else you forfeit the leftover money. However, employers have options (per IRS rules) to alleviate this a bit: they can offer either a grace period of up to 2.5 months into the next year to spend remaining funds, or allow a carryover of a limited dollar amount to the next plan year. They cannot offer both options, and they also don’t have to offer either – it’s up to the employer’s plan design. If a carryover is offered, the IRS set the maximum carryover at $660 that can be carried from 2024 into 2025. Any unused amount above that is forfeited. If a grace period is offered instead, typically you might have until mid-March of the next year to use the leftover before losing it.

With an FSA, you need to plan your contributions and spending carefully so you don’t lose money. Assume any unspent FSA money by the deadline will be lost (forfeited to your employer).

Portability #

Unlike an HSA, an FSA is owned by the employer.

If you leave your job during the year, your FSA generally ends. You can only use remaining funds for expenses incurred while you were employed (some plans offer a short runoff period to submit claims for expenses before your termination date). Any unspent money typically reverts to the employer. In some cases, you might have the option to continue a health FSA through COBRA (paying after-tax to keep access for the rest of the year), but this is not common in practice. So, FSAs are not portable – they do not move with you to a new job.

FSAs are truly “use-it-or-lose-it,” so always spend the balance of your FSA before you leave a job, or before the end of the plan year.

If you’re planning to leave your job before the end of your FSA plan year, keep in mind that the total amount you’ve elected for your Flexible Spending Account (FSA) is available immediately at the start of the plan year. Although your contributions are deducted gradually from your paychecks throughout the year, you have access to the entire balance from the beginning.

Therefore, if you anticipate leaving your job before contributing the full amount to your FSA, it’s beneficial to spend as much of your available balance as possible before your account is terminated. Doing so allows you to maximize your healthcare and wellness benefits, effectively turning your FSA funds into “free money.” Consider using these funds for eligible expenses like eyeglasses, pre-paying for wellness appointments or packages, and purchasing approved over-the-counter and wellness products.

Summary #

FSA is a useful short-term, tax-saving account for predictable expenses. It’s best for those who want to save on this year’s taxes for known medical or child care costs. You get an immediate tax break, but you need to be mindful of the use-it-or-lose-it rule. FSAs work well if you can accurately forecast things like annual medical copays, orthodontics payments, daycare tuition, etc., and thus set aside the right amount of money to cover them with pre-tax dollars.

What is a Dependent Care Flexible Spending Account (Dependent Care FSA or DCFSA)? #

A Dependent Care Flexible Spending Account (Dependent Care FSA or DCFSA) is a pre-tax benefit account used to pay for eligible dependent care expenses, like daycare, preschool, and summer camps. It’s a powerful tool to help working parents and caregivers save money while managing child or dependent care costs. A Dependent Care FSA is an employer-sponsored benefit that allows you to set aside money before taxes to pay for eligible expenses related to the care of dependents. It is different from a Healthcare FSA.

Eligibility #

You can use DCFSA funds for care of:

Children under 13 who live with you more than half the year.

Spouses or adult dependents (e.g., elderly parents) who are physically or mentally incapable of self-care and live with you.

Contribution Limits #

Annual Contribution Limit (2025):

$5,000 per household

$2,500 if married and filing separately

How It Works #

Enroll through your employer during open enrollment or after a qualifying life event.

Choose your annual contribution, up to the IRS limit.

Money is deducted from your paycheck pre-tax, typically spread evenly across the year.

Submit claims for reimbursement for eligible expenses you’ve already paid.

Note: Unlike healthcare FSAs, funds are not available upfront—you can only be reimbursed up to the amount that has been contributed to date.

Usage #

You can use your DCFSA funds to pay for care that allows you (and your spouse, if married) to work, look for work, or attend school full-time.

Examples of Eligible Expenses: #

Daycare or nursery school

Preschool (only the care portion, not education)

Before/after school programs

Nannies, babysitters (work-related care)

Summer day camps (overnight camps are not eligible)

Adult day care centers

Ineligible Expenses #

Certain expenses are not eligible, even if related to care:

Tuition for kindergarten and up

Overnight camps

Meals, field trips, or supplies

Care provided by your spouse, child under 19, or another dependent

Nursing home expenses

Babysitting when not work-related (e.g., date night)

Rollover: Use-it-or-lose-it

Funds must generally be used by the end of the plan year (some plans offer a short grace period).

Tax Benefits #

Pre-tax savings: Contributions are exempt from federal income tax, Social Security tax, and Medicare tax.

Tax Advantages

Dependent Care FSAs can offer significant tax savings—often 20% to 40% of your eligible expenses depending on your tax bracket.

Example:

You contribute $5,000 to a DCFSA.

You avoid paying roughly $1,200–$2,000 in taxes (federal, Social Security, Medicare).

DCFSA vs. Childcare Tax Credit

You cannot double-dip, but you can:

Use both the DCFSA and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit strategically.

Example: Use DCFSA for the first $5,000, then apply the credit to any additional qualifying expenses (if eligible).

Tips #

Estimate carefully. Unused funds are forfeited unless your plan has a grace period.

Keep documentation—receipts, invoices, provider details—for every claim.

Combine with healthcare FSA or HSA (if eligible) to maximize tax savings.

Summary #

A Dependent Care FSA is one of the most effective ways for working families to reduce the financial burden of caregiving. Understanding how to use it well can save you thousands per year and make child or dependent care more manageable.

What is a Lifestyle Spending Account (LSA)? #

A Lifestyle Spending Account (LSA) is a relatively new type of employer benefit that provides reimbursements for various wellness or lifestyle expenses.

Unlike HSAs and FSAs, LSAs are funded entirely by the employer – employees typically do not contribute their own money. Also, unlike the other accounts, LSAs are post-tax benefits (not tax-advantaged). The primary purpose of an LSA is to support employees’ overall well-being by covering costs that fall outside traditional health insurance or medical accounts, such as gym memberships, fitness gear, mental health services, and other quality-of-life improvements.

Eligibility #

You’re eligible for an LSA only if your employer offers one as part of the benefits package.

There’s no government mandate or individual account setup. The employer defines who can participate – it could be all employees or certain groups (for example, full-time employees only, or those who complete a wellness program, etc., depending on the company’s policy). There’s no requirement to have a particular health plan, since LSAs are unrelated to health insurance.

How It Works #

An LSA is essentially an employer-funded reimbursement arrangement.

The company allocates a certain allowance amount (say, a few hundred dollars per year) for each participating employee to spend on approved wellness or lifestyle expenses. Employees pay for the eligible services or items out-of-pocket, then submit proof of purchase (receipts) to get reimbursed from the LSA fund. Some employers might alternatively provide a prepaid benefits card or upfront funds, but reimbursement is most common. Employers have a lot of flexibility to customize the LSA design: they decide how much money is provided, what counts as an eligible expense, when/how often the allowance is given (e.g. a lump sum annually or a quarterly stipend), and what happens to unused funds at year-end.

Eligible Uses #

LSAs are extremely flexible in terms of what expenses can be covered, as long as the employer allows it. There is no fixed list by the IRS – each company sets its own eligible categories. Common LSA reimbursable expenses include:

Physical wellness: Gym or fitness class memberships, exercise equipment, sports league fees, yoga classes, personal training, wearable fitness trackers, etc.

Mental health: Meditation app subscriptions, counseling or coaching services, stress management programs, massages, mindfulness or relaxation classes

Financial wellness: Financial planning or budgeting courses, student loan repayment assistance, tuition for personal development classes

Work-life and productivity: Home office equipment, standing desks, ergonomic chairs, internet or cell phone bill stipends for remote workers

Family and life expenses: Childcare or elder care support, adoption or fertility assistance, pet care (pet insurance or dog walking), commuting costs, transit passes, parking fees, even entertainment or hobby expenses in some cases (like museum passes, language lessons, or concert tickets).

Each employer chooses what’s covered. Some companies focus their LSA on specific areas (for example, a tech company might emphasize wellness and continuous learning, while another might include family-care perks). The key is that LSAs cover things to improve your lifestyle, health, or well-being that aren’t typically covered by insurance or other benefit accounts. Always check your own employer’s LSA policy for the menu of eligible expenses.

Contribution Limits #

Unlike HSAs/FSAs, there is no IRS-imposed contribution limit for LSAs because they are not tax-free. Employers can decide how much to budget. Many employers pick an amount that fits their wellness budget or aligns with specific goals. As mentioned, a few hundred dollars per year per employee is common, but some might be more generous if covering big-ticket items (e.g. an employer might offer $5,000 for adoption expenses via an LSA). The absence of a legal cap means it’s entirely up to the company’s discretion.

#

Funding and Tax Treatment #

Only the employer can put money into an LSA

Employees do not contribute from their paychecks. Importantly, LSA reimbursements are generally treated as taxable income to the employee, because the IRS does not consider most LSA expenses to be tax-free benefits. In other words, an LSA is post-tax: you might see the reimbursement added to your paycheck (or W-2) and taxed, or the employer might gross up the amount. (A few specific types of expenses, like education assistance or certain transportation benefits, could qualify for existing tax exemptions – but in most cases, expect LSA funds to be taxable.) Even if it’s taxable, it’s still extra compensation earmarked for your personal development and wellness, which you wouldn’t otherwise receive. On average, companies that offer LSAs have provided around $500 to $1,000 per employee per year (one study cited $850 as an average), but this amount varies widely by employer and budget.

#

Rollover Rules #

Because LSAs are employer-defined, the treatment of unused funds varies. Typically, if the LSA is run on a reimbursement basis (you spend then get paid back), any unused allowance at the end of the plan year does not carry over – it just stays with the employer (since no cash actually changed hands unless reimbursed). Some employers might allow a grace period or even rollover of unspent balances for a certain time, but this is optional. It’s safest to assume “use it or lose it” within each year for an LSA unless your program specifically states otherwise. The company isn’t going to pay out unused LSA funds to you in cash (since that would defeat the purpose of being a targeted benefit). If you leave the company, any pending LSA balance is usually forfeited as well.

Portability #

LSAs are not portable because they’re not individual accounts

They’re simply a feature of your employer’s benefit and compensation plan. If you change jobs, you can’t take any remaining LSA money with you or continue to get reimbursed by your old employer, of course. It’s a “use it while you’re here” type of perk.

Summary #

A LSA is like a company-funded wellness stipend. It’s very flexible in what it can cover (from gym fees to gadget purchases to personal growth classes), but it’s taxable to you and is not meant for medical expenses that would go under an FSA/HSA. LSAs are purely a perk to enhance your lifestyle and well-being. If your employer offers an LSA, it’s a great opportunity to get reimbursed for activities or items that can improve your health, happiness, or productivity, at least up to the allotted budget.

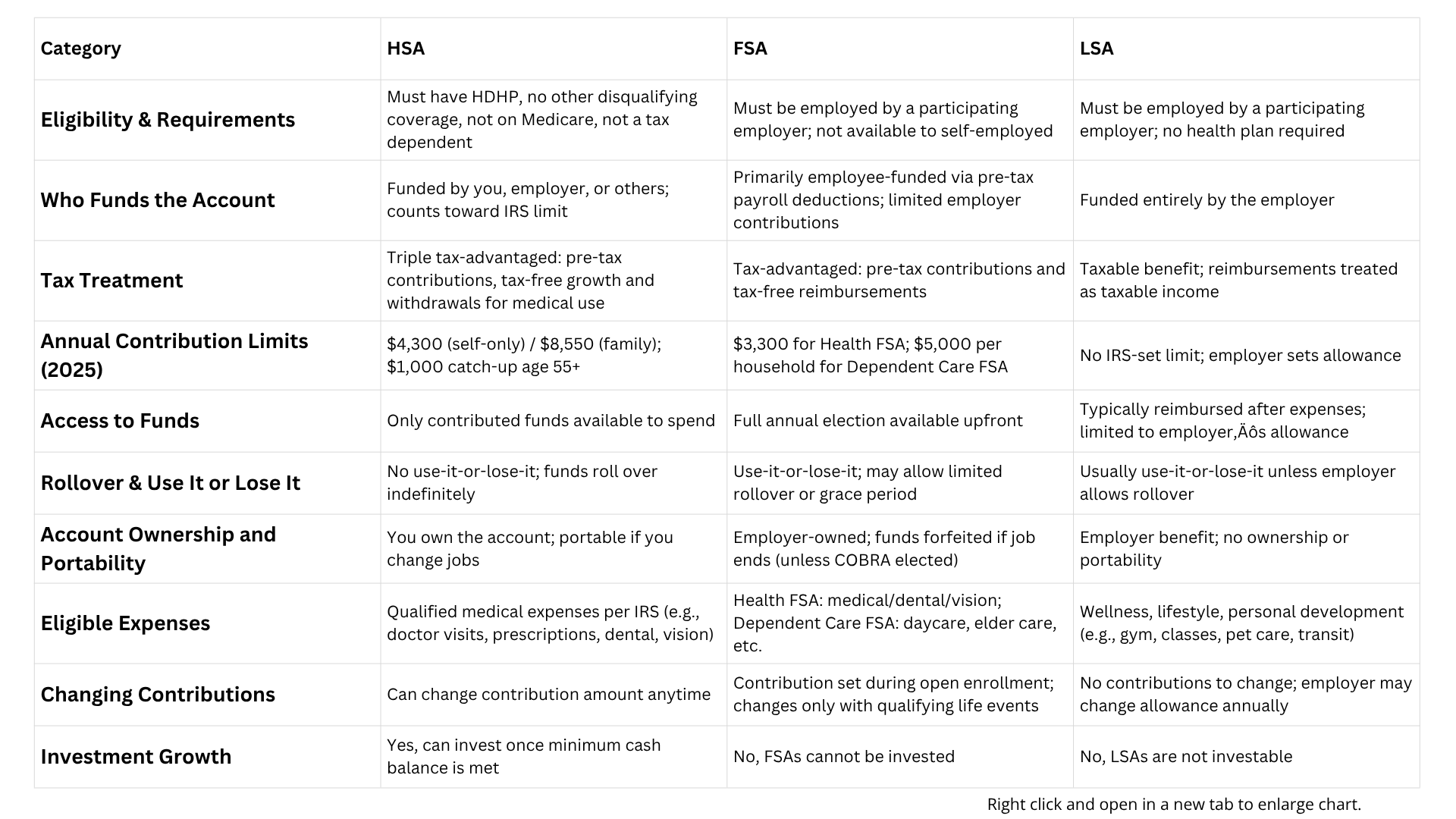

Comparing HSAs, FSAs, and LSAs #

HSAs, FSAs, and LSAs each have distinct features. The infographic below highlights key differences between HSAs and FSAs (the two tax-advantaged health accounts). Notice differences in eligibility, ownership, contribution limits, and rollover rules. LSAs, which are not tax-advantaged medical accounts, differ even further – for instance, only employers fund them and they cover non-medical expenses. We’ll outline LSA differences in the text that follows.

Key differences between an HSA and an FSA (LSAs differ further as described below).

Below is a side-by-side comparison of major factors for HSAs vs FSAs vs LSAs:

Eligibility & Requirements

HSA: Must be enrolled in a qualified high-deductible health plan (HDHP). Cannot have other disqualifying coverage (including a general-purpose FSA), and cannot be on Medicare or claimed as a tax dependent.

FSA: Must be an employee of an employer that offers an FSA. Available to most benefits-eligible employees; self-employed not eligible. No specific insurance plan enrollment required for Health FSA (though having any health plan helps ensure you have expenses to use it on!).

LSA: Must be an employee of an employer that offers an LSA program. No health plan or insurance requirements. The employer sets any additional eligibility rules (for example, might need to be full-time or have passed a probation period, depending on the plan).

Who Funds the Account #

HSA: Funded by you, your employer, or anyone on your behalf. Contributions can come from payroll deductions, lump sum deposits, or employer contributions like seed money or wellness incentives, all counting toward your annual limit.

FSA: Funded by you (the employee) via pre-tax payroll deductions. Employers may contribute in some cases, but it’s primarily employee-funded. Each spouse can have their own FSA through their jobs, but funds are not shared between spouses.

LSA: Funded entirely by the employer. Employees do not contribute. The employer allocates a certain dollar amount for each employee’s use.

Tax Treatment #

HSA: Triple tax-advantaged: contributions are pre-tax (or tax-deductible), growth is tax-free, and withdrawals are tax-free when used for qualified medical expenses. (Withdrawals for non-qualified expenses are taxed + 20% penalty if under age 65.)

FSA: Tax-advantaged: contributions are pre-tax (exempt from income and payroll taxes), and reimbursements for eligible expenses are tax-free. There’s no investment component, just tax-free in and out for spending within the year.

LSA: Taxable benefit: reimbursements are generally treated as taxable income to the employee (since they don’t meet IRS tax-free benefit criteria). The employer’s contributions are made post-tax. Essentially, LSA funds are like a bonus earmarked for wellness (the company may gross-up or just add it to your W-2). One exception: if an LSA includes something like educational assistance or certain transit subsidies, those specific pieces might fall under existing tax-free limits, but most LSA items are taxable.

Annual Contribution Limits (2025) #

HSA: Yes – limited by IRS. For 2025, up to $4,300 if you have self-only HDHP coverage, or $8,550 if you have family HDHP coverage. People age 55+ can put in an extra $1,000 (“catch-up” contribution). These limits usually adjust annually.

FSA: Yes – limited by IRS. For a Health Care FSA, the 2025 cap is $3,300 per employee (regardless of single or family status). Dependent Care FSA is capped at $5,000 per household (unchanged, set by law). Employers can choose lower caps for their plan, but not higher. You elect an amount up to the limit each year.

LSA: No federally set limit. The employer decides how much to offer. It could be $200, $1,000, or more – it’s up to the company’s budget and objectives. There’s no tax law imposing a maximum (since any amount is taxable to you anyway).

Access to Funds #

HSA: Only the money that has actually been contributed is available to spend. Your HSA balance grows as you and/or your employer deposit funds (much like a bank account). You can only use what’s in the account at that moment – no borrowing ahead from future contributions.

FSA: Full annual election is available upfront (for Health FSAs). If you elected $3,000 for the year, that full amount is accessible for claims on day one of the plan year, even though you haven’t contributed it all yet. (Dependent Care FSAs work on a pay-as-you-go basis; you can only get reimbursed up to what has been deducted so far.)

LSA: Typically, employees get reimbursed after spending their own money on eligible items. Some employers might fund an LSA account or card that can be drawn down, but commonly you submit receipts and the company pays you back up to your allowance. You can only get reimbursed up to the set allowance (e.g., if the LSA yearly cap is $500, that’s all you can use, and you can’t get more even if you have more eligible expenses).

Rollover & “Use It or Lose It” #

HSA: No use-it-or-lose-it – all funds roll over year to year indefinitely. There is no expiration on HSA money; unspent funds simply remain in your account for future healthcare needs. This allows balances to grow over time.

FSA: Use-it-or-lose-it applies. Generally, you forfeit any unspent money at the end of the plan year. However, your employer’s plan may offer either a short grace period or a carryover of a limited amount (e.g. $660 can carry from 2024 to 2025). Any excess beyond the allowed carryover is lost. It’s important to plan FSA contributions carefully to avoid forfeiture.

LSA: Usually use-it-or-lose-it for each plan year as well. Unused LSA allocations typically don’t carry over unless your employer explicitly allows some rollover. If you don’t use the available funds by year-end, the opportunity is gone (and the employer keeps the unspent money). LSAs are meant to encourage use of the benefits annually.

Ownership and Portability #

HSA: You own the HSA. It’s a personal bank account in your name. If you change jobs or retire, the HSA stays with you (you might lose the ability to contribute new funds if you’re no longer HSA-eligible, but the existing money remains yours). You can spend it down over your lifetime on eligible expenses.

FSA: Employer-owned arrangement. The FSA is tied to your employer. If you leave the company, any unused FSA funds are forfeited to the employer (unless you elect costly COBRA continuation for a health FSA). FSAs do not move with you between jobs. Each new employer, if they offer an FSA, means starting a new account/fresh election.

LSA: Employer-provided benefit, not a personal account. If you leave the job or the program ends, you can no longer use any remaining LSA funds. There’s nothing for you to “take with you,” since reimbursements were essentially company funds. It’s tied entirely to your employment.

Eligible Expenses #

HSA: Qualified medical expenses as defined by the IRS (the same types of expenses you could deduct on taxes or use an FSA for). This includes most out-of-pocket medical, dental, and vision care costs for you and your family. Common examples: doctor’s visits, lab tests, hospital bills, surgery, prescription drugs, insulin, over-the-counter medications and first aid supplies, therapy, dental treatments, eyeglasses, contact lenses, etc. HSAs are for health expenses only – you cannot use them for general wellness or non-medical costs.

FSA: Qualified health expenses (for Health FSA) – very similar list to HSA above, covering medical/dental/vision for you and dependents and/or Dependent care expenses (if you have a Dependent Care FSA) – which include daycare, babysitters, day camps, elder care facilities, etc., for a child under 13 or a disabled dependent so that you can work. Each FSA type’s funds can only be used for that respective category. Also, FSAs cannot be used to pay insurance premiums or cosmetic procedures, and any expense must be within the current plan year.

LSA: Wellness, lifestyle, and other personal development expenses as defined by your employer. Non-medical by nature. Typical categories include fitness (gym memberships, workout classes, equipment), wellness (nutrition programs, weight loss programs, mental health apps, massages), personal growth (educational courses, hobby classes), family and life (child or elder care support, pet care, travel or commuting costs, entertainment events). LSAs intentionally cover things that HSAs/FSAs do not, providing a broader definition of well-being. They generally cannot be used for expenses that health FSAs or insurance would cover (and if an expense is health-related, you’d usually use HSA/FSA for the tax break first).

Changing Contributions #

HSA: You can change your contribution amount at any time during the year (increase, decrease, stop, restart), as long as you don’t exceed the annual max. This offers flexibility if your financial situation or needs change.

FSA: You choose your annual contribution during open enrollment, and that election is locked in for the year. You generally cannot change it mid-year unless you have a qualifying life event (such as marriage, divorce, birth of a child, etc.) that allows an adjustment. This is why planning is important; you have to estimate your yearly expenses in advance.

LSA: There’s no contribution from your side, so nothing for you to change. The employer might adjust the allowance year to year, but as an employee you just use whatever amount is offered.

Investment Growth #

HSA: Yes, many HSAs allow you to invest funds in stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc., once you have a minimum balance (often around $1,000 or $2,000) in cash. Invested funds can grow and earn interest or gains tax-free, providing potentially significant long-term growth. An HSA can effectively become a supplemental retirement healthcare account thanks to this investment feature.

FSA: No, FSAs do not have an investment option. They are a simple spend-and-reimburse account, and the money does not earn interest. Since funds are short-term and forfeitable, there’s no opportunity or mechanism to invest FSA dollars.

LSA: No, there’s no investment component. The funds are not really “yours” to invest; they are just a reimbursement pool for expenses. Typically, you aren’t given the LSA money upfront to invest – you only receive it when you file a claim for reimbursement.

In summary, HSAs and FSAs share the goal of using pre-tax money for expenses but differ in ownership, flexibility, and longevity of funds. LSAs are a different animal altogether: a taxable employer perk for lifestyle benefits. HSAs are best viewed as a long-term personal health savings/investment account, FSAs as a year-to-year budgeting tool for predictable expenses, and LSAs as a wellness benefit to utilize for your personal improvement.

Tips and Best Practices for Maximizing Each Account #

Each account comes with strategies to make the most of it. Here are some practical tips to ensure you maximize the value of your HSA, FSA, and LSA:

HSA Best Practices #

Contribute the Maximum if You Can

If you can afford it, try to contribute up to the IRS limit each year (especially if your employer also contributes). This maximizes your tax savings and builds a larger balance for future needs. Every dollar in an HSA saves you on taxes and can grow over time. Remember that those 55 or older get an extra $1,000 in allowed contributions – take advantage of that “catch-up” if eligible.

Capture Employer Contributions

Many employers that offer HDHPs also contribute to your HSA (e.g., they might put in $500 for singles, $1,000 for families, or match some of your contributions). Be sure to enroll and put in enough of your own money, if required, to get the full employer contribution – that’s essentially free money. Just remember employer contributions count toward your annual limit.

Use It Now or Use It Later – Be Strategic

One great aspect of HSAs is that you don’t have to spend the money in the year you contribute it. In fact, an effective strategy is to pay for current medical expenses out-of-pocket (if you can afford to) and let your HSA money stay invested and grow tax-free for the future. You can later reimburse yourself from the HSA for those past expenses (even years later) since there’s no expiration on claims, as long as you keep the receipts. This way, your HSA can act like a supplemental retirement fund dedicated to health expenses. On the other hand, if you have high medical costs now and need the funds, don’t hesitate to use the HSA – that’s what it’s there for, and you’re still saving by using pre-tax dollars.

Invest for Growth

If your HSA provider allows investing and you have more money in the HSA than you expect to spend in the near term, consider investing a portion of it. Over decades, an invested HSA can grow significantly (just like an IRA or 401k), and all that growth is tax-free. Many people invest their HSA funds for long-term growth to use in retirement for healthcare (when medical needs may be greater). Just be mindful of keeping some liquid cash in the HSA for shorter-term needs and your deductible.

Keep All Your Receipts

Maintain good records of your medical expenses (receipts, Explanation of Benefits from insurance, etc.), even if you don’t reimburse yourself right away. You might decide later to take a distribution for an expense you incurred this year. Also, if the IRS ever audits HSA withdrawals, you’ll need to show they were for qualified expenses. Consider scanning receipts and storing them digitally for safekeeping.

FSA Best Practices #

Estimate Expenses and Plan Ahead

Before each annual enrollment, make a list of predictable health expenses for the coming year. This can include regular prescriptions, monthly therapy co-pays, anticipated dental work, new glasses or contacts, planned surgeries, or even routine over-the-counter items. Also consider big one-time costs you expect (e.g., having a baby, which could involve hospital co-pays). Do the same for dependent care costs if using a Dependent Care FSA. Use those estimates to decide how much to elect. It’s better to be slightly conservative (under-estimate) than to over-contribute and risk forfeiting money. Remember, you can’t change the amount mid-year without a qualifying life event, so plan carefully.

Take Advantage of the Tax Savings

Contribute enough to cover things you know you’ll spend on – it’s like getting a 20-40% discount on those expenses. For example, if you always spend $500 on contact lenses and solution annually, running that through an FSA saves you the taxes you’d otherwise pay on $500 of income. Over a variety of expenses, this adds up to real savings. Many people save hundreds of dollars per year by using FSAs for expenses they’d have anyway.

Use FSA Funds Wisely Throughout the Year

Since health FSA money is available upfront, you can schedule medical procedures or buy needed items early in the year. But also track your FSA balance as the year progresses. Halfway through the year, check if you’re on pace to use it all. If not, you may need to deliberately spend down the remainder (see next tip). If you are running low fast (and you don’t have other sources to cover further health expenses), be cautious about optional spending. For dependent care FSAs, ensure your daycare provider receipts match what you’re contributing, and adjust if, say, your child stops daycare mid-year (though you generally can’t change election, you might at least know if some will be unused).

Avoid Forfeiting Money (Spend It All)

As you approach the end of the year (or grace period), make sure to use up any remaining FSA funds. This might mean scheduling that dental cleaning or eye exam before year-end, stocking up on eligible over-the-counter medicines, buying a spare pair of glasses or contact lenses, or getting medical equipment (first aid kits, blood pressure monitor, etc.) that you’ve been putting off. Check the list of FSA-eligible items – you might find practical things at the pharmacy that are covered. Some plans allow a small carryover, but it’s wise not to rely on it; try to zero out your balance with legitimate expenses. Unused money will be lost, so it’s better to get some useful products or services with it than to forfeit it.

Keep Documentation & Use the Easiest Payment Method

If your FSA offers a debit card, use it for eligible purchases – it directly uses your FSA funds and often auto-substantiates the expense (especially at pharmacies or doctors where systems can flag eligible items). This saves you from paying out-of-pocket and then filing a claim. Still, save your receipts and EOBs because the FSA administrator might ask for proof for some transactions (especially bigger ones or ones that aren’t auto-verified). Submitting claims promptly for reimbursement (if you paid out-of-pocket) will ensure you get your money back quickly. Also note, some expenses might need a letter of medical necessity (for example, if you’re using FSA for something like a massage for a medical condition, your doctor should write a note). Organize these records in case of any issues or audits.

Consider the Dependent Care Tax Credit

If you have a Dependent Care FSA, compare its benefit to the federal childcare tax credit (you generally can’t double-dip both on the same dollars). The $5,000 through an FSA is pre-tax and usually more advantageous for many middle-to-high income earners. However, if you have more than $5,000 of child care expenses, you could use the FSA for the first $5k and still potentially claim the tax credit on the remainder. Consult a tax advisor for your personal situation, but don’t leave the Dependent Care FSA on the table if it’s offered and you have eligible expenses – it often yields greater savings than the credit for most people.

LSA Best Practices #

Know Your Allowance and Eligible Categories

First, make sure you understand how much your LSA gives you and what exactly you can use it for. Read the guidelines from your HR or benefits provider. Because LSAs are so customizable, every company’s program is a little different. Some might focus only on fitness and education, others might include broad wellness or even leisure activities. Knowing the rules will help you take full advantage and avoid submitting ineligible expenses. If you’re unsure whether something qualifies, ask HR or check any provided FAQ.

Use the Benefit – Don’t Let It Go Unused

This sounds obvious, but many employees forget to claim their LSA perks, especially if it’s a newer benefit. Treat the LSA allowance as part of your compensation – not using it is like leaving money on the table. If your employer gives $500 for wellness, challenge yourself to utilize it. Try out a class, buy that standing desk or set of dumbbells, or get a subscription that improves your well-being. Even if it’s taxable, you’re still getting a benefit you wouldn’t otherwise. Remember that any unused amount likely won’t carry over (unless stated), so plan to spend it within the year.

Save and Submit Receipts Promptly

Keep receipts for all your eligible purchases or payments. Mark them or store them in a folder (physical or digital). Submitting them as you go (monthly or quarterly) can prevent a last-minute scramble. There might be a deadline each year (or each quarter) to request reimbursement, so don’t miss that. Submitting promptly also helps you see how much of your allowance is remaining. Some programs have an app or portal – use those tools to make the process easier.

Try Something New for Your Well-being

LSAs are a great opportunity to do something beneficial for yourself that you might hesitate to spend your own money on. For example, if you’ve wanted to try a fitness class or consult a nutritionist, but cost was a barrier – use the LSA to cover it. Or maybe invest in ergonomic home office equipment to improve your comfort if you work remotely. Some employers even allow things like meditation retreats, music lessons, or language courses. Think creatively about what would improve your life, health, or skills, and see if the LSA can fund it. This not only uses the benefit fully but can greatly enhance your personal growth or wellness.

Be Mindful of Tax Implications

Since LSA benefits are taxable, be aware that if you use, say, the full $1,000 LSA, you will pay taxes on that $1,000 as if it were additional income. Your employer might handle this by withholding taxes on the reimbursement or by adding it to your W-2. It’s usually not a big issue (and certainly not a reason to avoid using the benefit), but it’s good to know. The net effect is you might see a few extra dollars of tax withholding. The value to you is the after-tax amount. For example, $500 LSA used might net you ~$350 if you’re in a ~30% combined tax bracket. It’s still $350 of stuff you got without spending your normal salary. Just don’t be surprised by the tax – plan for it as a necessary trade-off for getting the benefit.

Choosing the Right Account(s) for Your Situation #

With three different accounts on the table, you might wonder: Which of these do I need, and when? The answer can depend on your health insurance, your expected expenses, and what your employer offers. Here are some guidelines and scenarios to help you decide:

If you have a High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP)

Enrolling in the HDHP makes you eligible for an HSA, which is usually the best choice to take advantage of. HSAs are generally the top choice for HDHP participants because of their tax benefits and long-term value. If you’re comfortable with the higher deductible and can afford to set aside money, the HSA will help you cover that deductible and save for future costs. In fact, many financial advisors recommend maxing out your HSA each year if you can, before other retirement accounts, because of the triple tax advantage.

An HSA is ideal if you’re relatively healthy or can budget for routine care, and you want to build a healthcare war chest for later. Note: If you have an HSA, you cannot also contribute to a regular Health Care FSA. However, some employers offer a Limited-Purpose FSA (LPFSA) for dental and vision expenses only, which can be used alongside an HSA. If you expect significant dental or vision costs, and your employer provides an LPFSA option, you might consider electing that in addition to contributing to your HSA. The LPFSA still gives you pre-tax savings for those specific expenses without interfering with your HSA.

If you have a non-HDHP (traditional health plan)

You won’t be HSA-eligible, so an FSA is likely your primary tax-advantaged account for medical expenses. If your employer offers a Health Care FSA, it can substantially lower your out-of-pocket costs by letting you use pre-tax dollars.

FSAs are a great choice if you expect ongoing medical expenses

For example, if you or a dependent have regular prescriptions, therapies, planned surgeries, or simply routine copays and deductibles. Even if your costs are moderate, why not save 30% (your tax rate) on them? Just be mindful to not over-contribute. Generally, if you know you’ll have at least a few hundred dollars of eligible expenses in a year, it’s worth using an FSA. If your expenses are very unpredictable or minimal, you could opt to contribute a smaller amount or skip it, but many people find some predictable expenses (glasses, dental cleanings, OTC meds, etc.) that make an FSA worthwhile.

If you have significant childcare or dependent care expenses

Take advantage of a Dependent Care FSA if available. This is separate from the health FSA and can save you taxes on up to $5,000 of child care expenses per year. If you pay for daycare, preschool, after-school care, summer day camps, or an adult daycare for an elderly parent, a dependent care FSA is usually a no-brainer. It effectively gives you a discount on those expenses. One thing to consider: very low-income families might get more benefit from the dependent care tax credit, but for many dual-income families, using the FSA yields greater tax savings. You generally cannot double dip (can’t use FSA and also claim the same dollars for a tax credit). So if your expenses are under $5k, the FSA often wins; if well over $5k, you could use FSA for the first $5k and tax credit for the rest if eligible. But that’s a tax detail beyond the scope here – the main point is if your employer offers the Dependent Care FSA and you have dependent care costs, strongly consider using it. It will require some planning since funds are only available as contributed and you must file reimbursement claims, but the tax savings are worthwhile.

If your employer offers an LSA

There’s really no downside to using an LSA for whatever eligible items appeal to you. Since LSAs are purely employer-funded, it’s not a matter of choosing it over an HSA or FSA – it typically comes as an additional perk. Use your LSA to enrich your life or health in ways that matter to you. If you’re a fitness enthusiast, you might use it for new equipment or class passes. If you’ve been meaning to focus on self-care, maybe you get those massages or a meditation app subscription. If professional development is covered, perhaps take an online course that could advance your skills. The key is to not leave it unused. Some employees forget or feel hesitant to spend it – but remember, your employer wants you to utilize it for your well-being (that’s why they offered it). It can also introduce you to experiences or products you might not have tried on your own dime. The only consideration is the tax aspect – if using the LSA pushes you into a higher taxable income bracket (unlikely unless it’s a very large benefit), but for most people the impact is minor. In short, LSA vs no LSA – always take the LSA! There’s no trade-off with other accounts since it doesn’t affect your HSA or FSA eligibility.

HSA vs FSA – which one if I could choose?

Occasionally, someone might have a choice (for example, your employer offers two health plans: one HDHP with HSA, and one PPO with FSA). Or you might be deciding in a family where one spouse has an HSA option and the other an FSA. Here’s how to think about it:

HSAs have the edge in terms of tax savings and flexibility. The money is yours forever, it grows, and can become a substantial asset. But they require a high-deductible insurance plan, which might or might not be the best fit medically or financially in a given year. If you expect low to moderate healthcare usage and can handle unpredictable costs, an HDHP + HSA combo can pay off in the long run (with lower premiums and the HSA savings).

FSAs come with use-it-or-lose-it and no long-term accumulation, but they are available with more traditional health plans that have lower deductibles. If you anticipate higher medical expenses or simply value a plan with copays and lower out-of-pocket maximums, you might opt for the PPO-type plan and then use an FSA to cover the steady stream of costs. In terms of pure financial comparison: if you are healthy and won’t spend much, the HSA strategy can save more (and you bank the money). If you have chronic conditions or high expected costs, sometimes a traditional plan with FSA might reduce your immediate out-of-pocket exposure.

It can be a complex decision – some people actually calculate the worst-case and best-case scenarios of each plan. But one thing is sure: if you go the HSA route, contribute to that HSA because that’s where the value is realized. If you go the FSA route, don’t leave FSA money unclaimed – use it fully for maximum benefit. Some employers with HDHPs even contribute to HSAs to sway the value. Also consider family factors: e.g., if your spouse has an HSA family plan at their job and you could be on that, vs your job’s FSA – coordination matters. Generally, one cannot have both an HSA and a general FSA in the same household without restrictions (if one spouse has an HSA, the other’s general FSA could disqualify them unless it’s limited-purpose). So coordinate benefits with your spouse if applicable to avoid any IRS conflicts.

Multiple Accounts:

In some cases, you might use more than one account for different purposes. For example, you might have an HSA for medical expenses and also elect a Dependent Care FSA for child care, and simultaneously use an LSA for wellness. That’s perfectly fine because they cover different domains. Or, if you have an HSA, you could still use a Limited FSA for vision/dental as noted. You could also have a scenario where you use an FSA for medical and still have an LSA – again, that’s fine. Just be careful not to double-reimburse the same expense from two accounts (e.g., you cannot use both HSA and FSA for the same doctor’s bill – it has to be one or the other). Use each account for its intended expenses and maximize each one’s benefits independently.

In the end, the best account(s) for you depend on your personal situation: your health plan options, your expected expenses, cash flow, and whether your employer offers these benefits. If available, HSAs offer unparalleled long-term tax benefits and are great for future planning, FSAs offer immediate tax relief for known expenses, and LSAs offer a chance to improve your well-being on the company’s dime. Many employees will actually interface with two or even all three of these: for example, one might use an HSA for medical, a dependent care FSA for childcare, and get LSA reimbursements for gym classes – that would be maximizing everything! Consider your needs and use the above information to make informed decisions during open enrollment or benefits discussions. If unsure, consult your HR benefits counselor – they can clarify what combinations are allowed and how each account could fit your circumstances.

Additional Resources #

For more detailed information or guidance on HSAs and FSAs, check out these resources:

IRS Publication 969 – Health Savings Accounts and Other Tax-Favored Health Plans: Official IRS guide on HSAs and FSAs (and similar accounts), including rules, contribution limits, and qualified expenses. This is a comprehensive reference for the tax rules governing HSAs and FSAs.

Healthcare.gov – What are HSA-eligible plans?: Consumer-friendly explanation of HSAs, how HSA-qualified insurance works, and the benefits of an HSA. Helpful for understanding HDHPs and HSAs in plain language.

IRS News Release (Nov 7, 2024) – 2025 FSA Contribution Limits: Announcement of the updated FSA limits and carryover amounts. Good for checking the latest limits and reminders on FSA usage.